Dennis M. Hogan – Matter and the Idea: Hugo, Viollet-le-Duc, and the Nineteenth-Century Invention of Notre Dame

Une restauration peut être plus désastreuse pour un monument que les ravages des siècles et les fureurs populaires!

(A restoration can be more disastrous to a monument than the ravages of time and popular fury!)

––Jean-Baptiste Lassus and Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, Project de restauration de Notre-Dame de Paris

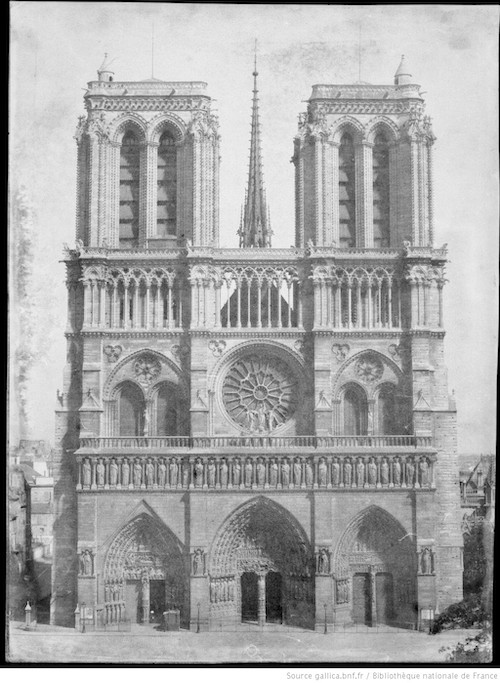

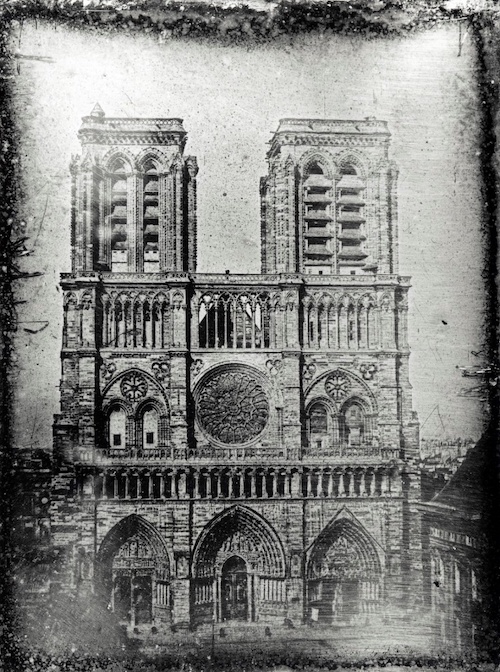

In the days following the fire at Notre Dame, Victor Hugo’s novel Notre-Dame de Paris shot to the top of French bestseller lists as news outlets told and retold the story of the novel’s effect on the restoration of the cathedral whose near-destruction occasioned a spontaneous outburst of public grief and public reprisal. That French readers turned to Hugo is only appropriate, for the relationship between the cathedral and the novel that bears its name offers perhaps the most famous single example of the profound exchanges that have long taken place between French literature and French Gothic architecture, a relationship that dominated European aesthetic and architectural thought through the nineteenth century, and, as the global response to the fire at the cathedral reflects, still determines our relationship to medieval monuments today.

In the wake of the conflagration, the French ruling class has risen to the challenge of rebuilding with surprising élan, pledging enormous sums dedicated to the massive rebuilding project. Critics have urged us to look harder at these spontaneous gestures of generosity, asking why billionaires can so readily find the money to rebuild national monuments, but not to address poverty, climate catastrophe, or the multiple migration crises and the global nativist backlash they have engendered. Clearly the image of the iconic structure in flames, and the videos of the spire collapsing, tug at wealthy heartstrings in a way that more quotidian evidence of human suffering just does not. If we want to know why Notre Dame, as structure, as symbol, as artistic patrimony, remains so powerful and still so politically contested, we ought to look not at the Middle Ages, which actually produced Gothic architecture, but at the nineteenth century, which, in a much more profound way, invented it.

Before Hugo’s novel appeared, the Cathedral had fallen into disrepair; though French revolutionaries were (and are still) often blamed for many of the worst abuses visited upon the structure, the combination of neglect and ill-advised intervention had accomplished more than the revolutionary mobs ever could. Hugo devotes long passages of Notre-Dame de Paris to lamenting these alterations, from the removal of the statues that had lined the façade to the dismantling of the spire in 1787. Indeed, even until the early nineteenth century the official aversion to the medieval was such that Napoleon’s coronation, which was celebrated inside the Cathedral, occasioned not only the total redecoration of the interior space in the classical style but also the erection of a painted classical façade on the exterior (Gilchrist 102). That Gothic architecture had been neglected and defaced during the early modern period reflected the low esteem in which the entire medieval period was held; by the early nineteenth century, however, aesthetic and intellectual currents had laid the groundwork for a reaction. The German Romantics had discovered the Teutonic Middle Ages as the source of Christian genius and Gothic emotion; Walter Scott’s historical romances had accomplished something similar for the British Middle Ages. Chateaubriand and Madame de Staël brought German Romantic ideas to France, while the first volume of Charles Nodier and Isidore Justin Taylor’s Les Voyages pittoresques et romantiques dans l’ancienne France appeared in 1820 (Emery 13). The book, an important French product of the Romantic ruin cult, offered richly-illustrated, often imaginative scenes of medieval architectural sites. Though new volumes of Les Voyages would continue to appear through 1878, the early editions contributed enormously to the establishment of a new architectural and aesthetic vocabulary that highlighted Gothic architecture as part of an autochthonous and demotic artistic tradition.

Ruines de l’Abbaye de Jumièges. Coté du Nord. Voyages pittoresques et romantiques dans l’ancienne France. Ancienne Normandie. Vol. 1 (1820) Charles Nodier, Isidore Justin Séverin Taylor & Alphonse de Cailleux

Fragmens, Abbaye de Jumièges. Voyages pittoresques et romantiques dans l’ancienne France. Ancienne Normandie. Vol. 1 (1820) Charles Nodier, Isidore Justin Séverin Taylor & Alphonse de Cailleux

Hugo’s novel contributed a new popular spirit to the existing discourse about medieval architecture. In Hugo’s mind, the cathedral was not merely a picturesque remnant, but a living testament to the progress of history and of the role of ordinary people in making that history happen. Gothic architecture emerges as a consequence of the progressive liberation of the individual from the theocratic structures that had previously dominated European life; the ornamentation and lack of proportionality that critics had singled out for scorn becomes evidence that the domination of theocratic Catholicism had given way to greater individuality of thought and spirit. Gothic experimentation reflects the social changes that took place throughout the High Middle Ages:

The cathedral itself, once so dogmatic a building, from now on invaded by the citizens, by the commons, by liberty, escaped from the priest and fell into the artist’s power. The artist builds in his own way. Farewell to mystery, myth, law. Enter fancy and caprice. Provided the priest has his basilica and his altar, he has no more say. Four walls belong to the artist. The book of architecture belonged no more to the priesthood, religion, Rome, but to imagination, poetry, the people. Whence the countless swift transformations of this architecture, only three centuries old, so striking after the stagnating immobility of Romanesque architecture, which was six or seven centuries old. (196)

In Hugo’s novel, the medieval cathedral in general and Notre Dame in particular is read as a priceless book of ideas, more durable than manuscripts, yet not nearly as indestructible as mechanically-reproduced texts, that became the privileged site for expression of popular thought and ideas in the centuries immediately preceding the invention of the printing press. Hugo popularizes a new, secular vision of the cathedral, and medieval religious architecture becomes worth saving because it contains evidence of precisely the kind of thinking, and the kind of human freedom, that will lead to the eventual overthrow of medieval theocracy and even the feudal domination that succeeds it. Naturally, these developments pave the way for the rise of bourgeois rule that would, only a year before the publication of Notre-Dame de Paris, install Louis-Phillippe as constitutional king, with the support of Hugo and much of the French population.

That the novel resulted in restorative action is by now well known. Ten years later, the July Monarchy would authorize a competition for the restoration of Notre Dame. Hugo would sit on the panel of judges that awarded the commission to the team of Jean-Baptiste Lassus and Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. Lassus died before the completion of the restoration work, but Viollet-le-Duc, more than any other figure, would go on to become the greatest proponent of French Gothic architecture’s value as artistic and cultural history in his or any other century. More importantly, Viollet-le-Duc would produce a body of practical and theoretical literature that would define the idea of the Gothic for years to come.

Viollet-le-Duc set about to correct every one of the injustices and mutilations that Hugo had identified, and then some. The purpose of the restoration was neither to return the building to its original form, nor to finish or complete it, but rather, as the Minister of Justice and Religious Affairs Martin du Nord explained, to “consolidate the parts threatened with destruction, to reestablish the architectural objects destroyed by time or mutilated by the hands of man, to purify the interior of the basilica of all the profanations of bad taste, in order to arrive at a sensible and properly conceived restoration.”[1] What can du Nord have meant by purifying the interior? Who decides which elements have been added in bad taste, and which instead contribute to bringing out the true spirit of the building? Who decides whether the restoration is sensible, whether it was properly conceived?

Viollet-le-Duc had already begun to formulate his own theories of Gothic architecture: the Gothic, he maintained, was defined in part by the style of decoration, but more importantly, by its rational construction. His nine-volume Dictionnaire raisonné de l’architecture française du XIe au XVIe siècle lays out this view, offering, alongside a minute description of the architectural features of secular and ecclesiastical constructions of the Middle Ages, a painstaking account of the ways that the different built elements fit together, each perfectly suited to its function, each employed where appropriate and only where appropriate. In Volume 8 of the Dictionnaire, Viollet-le-Duc defines restoration: “To restore a building is not just to preserve it, to repair it, and to remodel it, it is to re-instate it in a complete state such as it may never have been in at any given moment.”[2] Such a theory of restoration—any theory of restoration—gives the restorer enormous power. As Viollet-le-Duc observes, restoration is itself a modern phenomenon; while buildings had previously been altered or added to, only the historically-obsessed nineteenth century could have produced the idea of undertaking a vast construction project to return a building to an idealized earlier state.

Though Viollet-le-Duc and others celebrated the Gothic for its mutability, he had a specific sense of what kind of Gothic architecture was most important to preserve. This was the High Gothic style, in vogue through the twelfth and thirteenth centuries (Pevsner 9). This style originated in the Île-de-France, historic domain of the French kings, before becoming generalized through the rest of Europe. The original construction of Notre Dame began in 1163 and was completed in 1345, spannig nearly the entire length of the historical dominance of High Gothic. It represented, in this sense, a perfect candidate for Viollet-le-Duc’s attention. To preserve and restore this cathedral, not as it had been designed, nor as it had been when it was completed, nor with the intention of conserving later additions and alterations, was to reframe the church as a living monument to the architectural style that Viollet-le-Duc found most beautiful, and not coincidentally, most French. Notre Dame, the episcopal church of the French capital, had always had an intimate connection with the rituals of political power; Viollet-le-Duc singlehandedly connected its image to the ideological projection of the French state in a remarkably durable way.

Begun under the bourgeois constitutional monarchy of Louis-Philippe, continued during the brief Second Republic, and finally completed during the Second Empire, the restoration of Notre Dame (and of French medieval monuments generally), proved one of the few government policies that the midcentury regimes could agree on. Viollet-le-Duc himself avoided falling afoul of any of the governments in power; content to work under the Republic, he became intimately associated with the imperial court, before fleeing the Commune’s death sentence and eventually returning to Paris during the Third Republic to extol the particularly republican virtues of French cathedrals. We might read him cynically as a man both deeply connected to the political establishment and yet totally at ease with whichever government happened to be in power; or else, more idealistically, as a man committed to an idea of France and French cultural contributions that transcended that country’s revolving door of nineteenth-century governments. Whatever the reason, Viollet-le-Duc succeeded not only in establishing the Gothic cathedral as the single most important site of French cultural memory, but of connecting its ideological significance to almost every mainstream political current. Indeed, Notre Dame as a symbol of Frenchness has outlived any of the nineteenth century regimes, remaining as connected to the world’s image of France as that other nineteenth-century monument, the Eiffel Tower.

Yet this ideological reimagining has come at a cost: just as Hugo had written of the emergence of Gothic architecture, the cathedral has remained only secondarily a site of Catholic worship. The priests and the bishops have their altar, but scarcely much more. At the same time, the architecture celebrated by both Hugo and Viollet-le-Duc as the greatest achievement of ordinary workmanship and the most complete record of medieval popular thought remains tied to both Church and State. Contemporary aestheticization of Gothic architecture serves to contain the very democratic impulses the buildings were imagined to reflect. We might laugh at the crude jokes, drunk priests, embarrassed princes, and fornicating bishops depicted in the stone reliefs, but no one seriously suggests that earthly powers be actually overthrown. If we blame the French revolutionaries imagined to have destroyed Notre Dame the first time around, it is because they lacked the bourgeois capacity for aesthetic appreciation that would develop over the course of the nineteenth century: they read the cathedrals as monuments of power, not total art objects.

And indeed, Notre Dame remains a monument of power, though one of political power masquerading as “mere” cultural power. The loss imagined by hordes of distressed commentators, from the weeping Parisian crowds, to the French billionaires moved to sudden and uncharacteristic philanthropic munificence, to the thousands of individuals who donated to the restoration funds—from across the world, but especially from the United States—was the loss of a cultural symbol imagined to have stood resolutely unaltered for hundreds of years, guarding over the city like a benevolent watchman. Never mind that the collapsing spire was less than two centuries old; never mind that many of the statues in the portals were hewn from stone in nineteenth-century workshops; never mind that the gargoyles who have become metonyms of the structure, printed on the covers of Hugo’s novel and sold in tchotchke form across Paris, were themselves entirely products of Viollet-le-Duc’s imagination, and that no such grotesques had ever before been seen on any example of French Gothic architecture.

The structure of the cathedral has been saved, but it is the ideology of the French nation that stands imperiled, even if, as the response to the fire shows, it has retained its power to stir emotion and move people to action. The litany of real and perceived threats to the nation-state in general and the French nation-state in particular is long and need not be exhaustively repeated here, but, as people turn anew to nations and nationalism as a simplistic response to a world beset with complex and interrelated crises, we might speculate that, in viewing images of Notre Dame burning, they saw France itself aflame. Viollet-le-Duc wrote of Gothic architecture in his Dictionnaire Raisonné that “[d]ans l’architecture gothique, la matière est soumise à l’idée”; in Gothic architecture, matter is subject to the idea. Matter submits to the idea. Matter itself recognizes the superior claim of the idea before it and retreats. This is as true of our imaginations of the Gothic as of the materiality of the structures themselves. Viollet-le-Duc managed, like other ideologists of nationhood, to make his most modern gestures seem timeless, grafting onto an ancient structure an entirely contemporary ideology. This was the idea of Frenchness, one of the most successful examples, ever, of what the French call le marketing.

[1] “consolider les parties menacées de destruction, de rétablir les pièces d’architecture détruites par le temps ou mutilées par la main des hommes, de purifier l’intérieur de la basilique de toutes les profanations du mauvais goût, afin d’arriver à une restauration sage et bien entendue” (qtd. in Auzas, 180).

[2] Restaurer un édifice, ce n’est pas l’entretenir, le réparer ou le refaire, c’est le rétablir dans un état complet qui peut n’avoir jamais existé à un moment donné. (Qtd. in Pevsner 38)

Works Cited

Auzas, Pierre-Marie. “Viollet-le-Duc et la restauration de Notre-Dame de Paris.” Actes du Colloque International Viollet-le-Duc Paris 1980. Edited by Pierre-Marie Auzas. Paris: Nouvelles Editions Latines, 1982.

Emery, Elizabeth. Romancing the Cathedral: Gothic Architecture in Fin-de-Siècle French Culture. Albany, SUNY Press, 2001.

Gilchrist, Agnes Addison. Romanticism and the Gothic Revival. New York: Richard R. Smith, 1938.

Hugo, Victor. Notre-Dame de Paris. Trans. Alban Krailsheimer. Oxford and New York: Oxford UP, 1999 (1993).

Lassus, Jean-Baptiste and Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc. Projet de restauration de Notre-Dame de Paris : rapport adressé à M. le Ministre de la Justice et des Cultes. Paris: Imprimerie de Mme. de Lacombe, 1843.

Pevsner, Nikolaus. Ruskin and Viollet-le-Duc : Englishness and Frenchness in the Appreciation of Gothic Architecture. London: Thames and Hudson, 1969.

There are no comments yet.