David Coombs, Descriptive Turns in the Victorian 21st Century

The V21 manifesto charges Victorian Studies with having fallen prey to positivist historicism, a critical malady whose primary symptom is the aim to exhaustively describe the past.[i] On my own reading, positivist historicism is what remains after New Historicism runs out of steam. The New Historicism electrified criticism with the touch of the real by “making the literary and the nonliterary seem to be each other’s thick description.”[ii] But once that protocol became routine it left us constantly looking for the meaning of a literary text in the historical archive, with the result that we tend to see our literary objects of study as meaningful only within the context of the Victorian period. As an alternative to this tight periodization, the manifesto proposes a renewed attention to literary form, both for its capacity to travel easily between periods and in order to reaffirm the distinctively literary focus of English as a discipline.

The formalism of V21’s critique of historicism and vision for the discipline is distinctly at odds with the most influential critical challenge to historicism over the last decade, which generally goes by the name of the descriptive turn. This umbrella term gathers together a loose group of approaches—nonfigural reading, thin description, Actor Network Theory, object-oriented ontology, and so on—all of which share a key principle: that there is, in fact, something outside the text, a real that the text describes or gives some account of. These descriptive approaches distance themselves from New Historicism in the name of this real. The method of thick description that New Historicism adapted from Clifford Geertz’s interpretive anthropology aspires first and foremost to read cultures as texts. New Historicism wanted the touch of the real, but just a touch. The new descriptive approaches, on the other hand, want something more rigorous, something best captured by Eve Sedgwick back in 1997 as “a fresh, deroutinized sense of accountability to the real.”[iii]

Descriptive criticism sees a very different disciplinary future, one in which English has grown much closer to the sciences. Thus Heather Love argues that demonstrating the usefulness of techniques like close reading for scientific efforts to understand reality will help shore up the eroding position of English at a time when appeals to its traditional justifications in ethics and civics have lost their force.[iv] The exciting work by descriptive critics like Love does, I think, offer us an opportunity for some kind of rapprochement with the sciences after the disciplinary hostilities of the 90s. In the current climate of fiscal austerity, successful arguments for English may very well hinge on our being able to convince and make common cause with our colleagues from other fields in the modern university.

In this piece, I’d like to think about how the renewed formalism called for by V21 might be combined with descriptive criticism. I want to suggest that we already have models for what that kind of approach might look like, both in recent scholarly work and, less obviously, in Victorian aestheticism. With its self-conscious opposition to mimesis, its luxuriating in artificiality and the figurative, aestheticism might seem to have little to offer to a descriptive critical enterprise like nonfigural reading. But description is a major component of aestheticist writings. In texts like À rebours or the eleventh chapter of The Picture of Dorian Gray, the forward momentum of plot grinds to a halt as the narrative gets immersed in the meticulous description of aesthetic objects. Taking these descriptions more seriously as descriptions will, I think, help return our attention to form while also addressing two problems for the methodological aims and disciplinary vision of descriptive criticism.

The first problem lies in the way descriptive criticism both does and does not make the case for the importance of our objects of study: literary texts. There’s been no shortage of critics eager to proclaim the value of literature for the effort to describe reality. Bruno Latour even points to literary writing as a model for sociology, arguing that sociologists “should be inspired in being at least as disciplined, as enslaved by reality, as obsessed by textual quality, as good writers can be.”[v] But Latour clearly has one specific genre of literary writing in mind here, since only for literary realism would reality loom large enough to enslave. And this focus on realism is highly characteristic. Descriptive criticism tends to take realist writings as its main objects of inquiry, borrowing a certain transitive force from them in its search for the real. Love, for instance, turns purposefully to the most flatly realist passage in Beloved to offer her own model of what a thinly descriptive reading looks like.[vi] Meanwhile, the nonfigural reading that Elaine Freedgood and Cannon Schmitt have recently called for concentrates on Barthes’ reality effects, the insignificant descriptive notations that are a text’s primary means of proclaiming its faithfulness to reality.[vii] As important as realism is, especially for the study of Victorian literature, it’s not the only game in town. In its focus on realism, descriptive criticism runs the risk of excluding a good bit of literature from their justifications of the field. Aesthetic descriptions can help here by challenging us to accurately describe aesthetic objects themselves, in this way broadening the scope of descriptive criticism to include texts that don’t make straightforward claims to realism.

The second problem for descriptive criticism—stemming from its preference for empirical events over structures—is best approached with an account of how these new descriptive methods diverge from the thick description of New Historicism. For Geertz, whose anthropology was foundational for New Historicism, thick description is a method of textualization that makes it possible to “read” cultures by transforming empirical events, fleeting and singular, into an abstract ensemble of meanings and intentions.[viii] Ethnographers thus use thick description not to describe the experiences making up their observations in the field but rather as a means of “uncovering the conceptual structures that inform our subjects’ acts.”[ix] New Historicism, in adopting thick description, pursues something similar. New Historicist critics typically press their virtuoso readings of individual texts into the service of revealing the social logic that organizes a particular historical mentalité.

Descriptive critics seek alternatives to thick description that would resist turning empirical events into cultural texts. Love’s thin description, for example, attempts to “detextualize” events by digging them out from under the conceptual structures thick description piles on top of them.[x] Freedgood and Schmitt’s nonfigural reading similarly seeks to open textuality to the flow of “nontextual” events like Conrad’s tides.[xi] Descriptive criticism is thus very good at accounting for empirical events, but that very strength has left it vulnerable to the charge that it is less capable of grasping the larger structural processes at work in events—something that Marxism and historicism are both particularly good at.[xii] The vast scale of the two great resource-crises of our time—global warming and the skyrocketing inequalities of global capitalism—render them unpresentable to direct experience as discrete events but they are both very urgent concerns. These criticisms, I think, apply more to some versions of descriptive criticism than others.[xiii] But here, too, I want to suggest, aesthetic descriptions can offer us a model for interrogating the vexing relationship between event and structure.

Are the descriptive passages of aestheticist writing themselves amenable to thin description? Aestheticist descriptions would seem to be ripe for some kind of nonfigural reading. Like Jane Eyre’s mahogany furniture or Conrad’s nautical terms, the precise, referential specifications of such passages have typically received little attention from critics eager to unpack their figurative significance. So, in Epistemology of the Closet, Sedgwick reads the aesthetic descriptions of Dorian Gray’s chapter 11 as figures for a consumerism that, in turn, figures the fascination and dangers of queer mutual recognition at the fin du siècle.[xiv] In a way that is exemplary of the suspicious reading she would shortly distance herself from, Sedgwick’s reading of Dorian Gray proceeds steadily up the vertical axis of metaphor, away from the material objects described in the novel and towards the high dramas of social relations and subjectivity. But here we’re given warrant to read in just this fashion by no less an authority than Wilde himself, who after all argues in The Critic as Artist that the highest criticism is concerned not with fidelity to the object but rather to the personal experience of the critic, and therefore a mode of seeing the object as in itself it really is not. It’s just this utter subordination of descriptive accuracy to aesthetic effect that led Barthes to distinguish the long tradition of ekphrasis from the reality effects of modern realism.[xv]

Nonetheless, Wilde’s gleeful inversion of Arnold’s dictum that criticism sees the object as in itself it really is shouldn’t blind us to the Aesthetic Movement’s complex negotiations with objects and objectivity. Consider Pater’s widely anthologized account of La Gioconda, which Wilde cites as a model of criticism as art. Certainly, Pater’s rhapsodic description of the Mona Lisa as a vampire seems less than keenly invested in descriptive accuracy. But what is actually vampiric about the Mona Lisa for Pater is the way her figure embodies the longue durée of human history, telescoping global processes occurring over thousands of years down into a single moment of sense experience. Pater’s description of La Gioconda in fact culminates his essay on Leonardo by adopting the painter’s own method. Leonardo, in Pater’s narrative, early on abandons the “objective” painting of his mentors to learn “the art of going deep”—of diving “far below [the] outside of things” in search of their unseen sources.[xvi] (The terms of Pater’s essay are at times almost distractingly similar to contemporary debates around reading surfaces and depths.) The beautiful figures populating Leonardo’s paintings are ideal types through which he attempted to bring the ideas he fetched from the deep back to the surface of form and color. But while La Gioconda could be mistaken for a depiction of Leonardo’s ideal of feminine beauty, it is also, Pater emphasizes, a portrait of a real person. In an uncanny way, La Gioconda brings together a sensory object with theoretical abstractions. What, Pater asks, was “the relationship of a living Florentine to this creature of his thought? By what strange affinities had the dream and the person grown up thus apart, and yet so closely together?”[xvii]

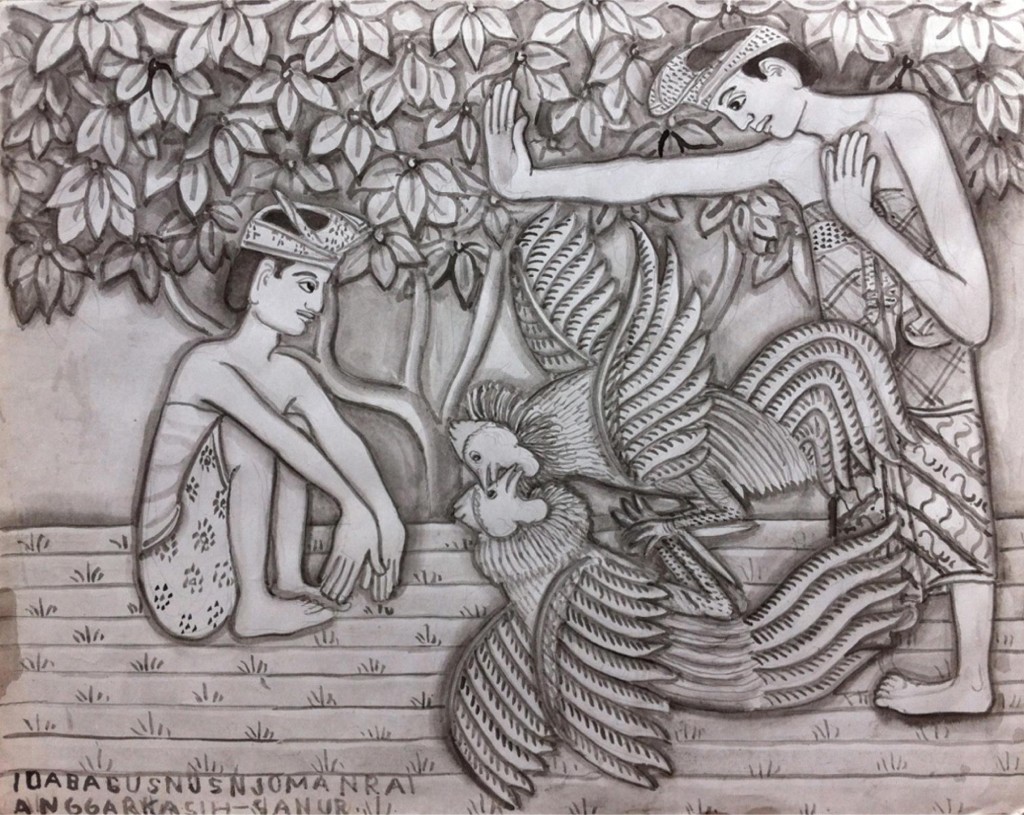

The strange affinities between model, painting, and description in Pater’s “Leonardo,” I suggest, challenge us to attend more closely to the strange affinities in play when the object of a description is, as is the case in our discipline, an aesthetic object. Pater’s essay asks us to think about how these strange affinities might take on very different forms in Geertz’s famous thick description of Balinese cockfighting and, say, a description of Cockfight, the ink drawing made by Balinese artist Ida Bagus Nyoman Rai at almost the same time that Geertz was doing his fieldwork there. Some recent scholarly work already points the way here by examining the strange affinities between the material of an artwork and its form,[xviii] or between an aesthetic object and the larger networks of forces determining it,[xix] or between a text and its individual material instantiations and readings.[xx] Each of these projects offers a model of how we might bring together the fresh sense of accountability to the real that makes descriptive criticism so exciting with the disciplinary commitment to the literary called for V21. In his essay on thick description, Geertz warned that if his interpretive anthropology lost sight of biological and physical necessities, it would risk turning “into a kind of sociological aestheticism.”[xxi] Here too, it seems, we are already living in the world the Victorians made, writing our descriptions, thick or thin, in the shadow of Pater and Wilde. We might as well make the most of it.

[i] I should note that Devin Griffiths compellingly argues that the label positivist historicism is unfair to both 19th century historicism and Comtean positivism here.

[ii] Stephen Greenblatt, “The Touch of the Real,” Representations 59 (1997): 14-29.

[iii] Sedgwick, Novel Gazing, (Durham: Duke U P, 1997), 2.

[iv] See Heather Love, “Close Reading and Thin Description,” Public Culture 25.3 (2013): 401-434.

[v] Latour, Reassembling the Social, (Oxford: Oxford U P, 2005), 126.

[vi] Love, “Close But Not Deep: Literary Ethics and the Descriptive Turn,” New Literary History 41.2 (2010): 371-391.

[vii] See especially Freedgood, The Ideas in Things, (Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2006), 9-12.

[viii] On singularity, see Ronjaunee Chatterjee’s V21 piece here.

[ix] Clifford Geertz, The Interpretation of Cultures, (New York: Basic Books, 1973), 27. Geertz draws here from Paul Ricouer, “The Model of the Text: Meaningful Action Considered as a Text,” New Literary History, 5.1 (1973): 91-117.

[x] Love, “Close Reading and Thin Description,” 430.

[xi] Elaine Freedgood and Cannon Schmitt, “Denotatively, Technically, Literally.” Representations 125.1 (2014): 9.

[xii] Lesjak, Carolyn. “1750 to the Present: Acts of Enclosure and Their Afterlife.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. May 1, 2015.

Lauren Goodlad and Andrew Sartori, “The Ends of History: Introduction.” Victorian Studies 55.1 (2013): 591-614.

[xiii] Nonfigural reading, in particular, self-consciously cashes out its attention to material objects and events (Jane Eyre’s furniture, Conrad’s tides) with conclusions about the larger processes transcending them (imperialism and narrative).

[xiv] Sedgwick, Epistemology of the Closet, (Berkeley: U of California P, 1990), 174-5.

[xv] Roland Barthes, The Rustle of Language, trans. Richard Howard, (New York: Hill and Wang, 1986), 143-4.

[xvi] Pater, The Renaissance, (Berkeley: U of California P, 1980), 81, 88.

[xvii] Ibid., 98.

[xviii] Siegel’s essay explores how the Victorians’ increased access to classical sculptures on the continent put new pressures on the long tradition of ekphrasis that had previously mediated such experience and led art critics like Lee to rethink the relationship between the material making up artworks and their form. See “The Material of Form: Vernon Lee at the Vatican and Out of it,” Victorian Studies 55.2 (2013): 189-201.

[xix] This is one of Pater’s key concerns on Benjamin Morgan’s reading. See “Aesthetic Freedom: Walter Pater and the Politics of Autonomy,” ELH 77.3 (2010): 731-756.

[xx] Bill Brown’s recent piece on this question is particularly suggestive in its refusal to accept a stark binary between matter and meaning or abstract concepts and material objects. See “[Concept/Object] [Text/Event],” ELH 81.2 (2014): 521-552.

[xxi] Geertz, 30.

There are no comments yet.