John Patrick James: Blake in/of Time: Presentism and Literary Form

In her introduction to “The Way We Write Now,” Caroline Levine notes several fissures in the logic of positivist historicism, one “version of historicism” which “assumes that genuine knowledge” derives “only through observation.” That principle, coupled with a “steadfast effort to separate [the] past from the interests and values of the present,” defines what she identifies as an overarching trend in mainstream historicism, one wherein the past is knowable only by its material trace and held at a distance because of this method’s radical emphasis on specificity. That many of today’s Victorianists have inherited this deeply empiricist mode of imagining the past as pure difference cuts against what Anna Kornbluh and Benjamin Morgan identify in their own introduction, “Presentism, Form, and the Future of History,” as the “robust interpretive mode” that epitomizes presentism. The sheer ubiquity of historicism as itself an interpretive mode begs us to reconsider what it offers to our field and what applications or uses it might hold.

I approach this problem as a Blakeist, someone whose focus falls just before the period of most contributors in the V21 collective but not so removed as to be unfamiliar with the field’s challenges. It’s a concentration embedded in material culture, since Blake, a poetic and visual artist, meticulously designed and printed his own illuminated books. For that reason, Blake studies is dominated by a positivist historicism entrenched in hyper-specificity—in the material composition of Blake’s work and in the methods by which those works were produced. Somewhat paradoxically, this trend has been invaluable for presentists, many of whom seek to combine historically particularizing readings of archival work with theories of empire, ecology, economics, etc. But a historicism with no mind for the present—one that collects information merely for the sake of having it—is one predicated on the “separability” Levine argues is essential to positivism: a division of “subject from object, one culture from another, Victorians from the twenty-first century.”

This tendency to separate the past from the present works against the combinatory temporality Blake himself advocates in “Auguries of Innocence,” where he writes, “To see a World in a Grain of Sand / And a Heaven in a Wild Flower / Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand / And Eternity in an hour” (1-4). The lines conflate space and time, thinking materiality in partition from time, which delimits being. As Blake sees it, all beings adopt physical form, but physicality is subject to the ravages of time, which ushers forward with unrelenting rapidity. It is the task of the maker, as Northrop Frye articulates, to see “images as permanent living forms outside time and space” even while giving them form through acts of historically-located poiesis (85). To truly read Blake, one must account for this temporal collision—a vision of diachrony ensconced within synchronicity itself—considering the ways by which the universality of thought becomes manifest in the ephemerality of material form.

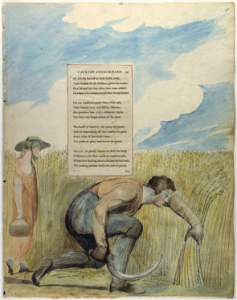

Fig. 1 “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard,” Page 5. Pen and ink, watercolor over pencil. c. 1797-98. Yale Center for British Art. (Image taken from the Blake Archive.)

In an effort to exemplify such an interpretive mode, I offer a brief reading of Blake’s illustrations to Thomas Gray’s “Elegy in a Country Churchyard” (Gray 1751, Blake 1798), a text that embodies Blake’s radical thought in content and form. Unlike his illuminated books, the Gray illustrations are sketched in pencil and painted in watercolor, allowing colors to run and sometimes mix. Subjects blend with their environments, pitting manual laborers against the natural backgrounds they penetrate with their tools. Figure one, for instance, features a farmhand bending low to the ground, holding back a clump of wheat with one hand and preparing to scythe it with another. The bend of his spine fashions an arch nearly symmetrical with that of the scythe, such that, when his right arm swings forward to cut the wheat, it might form a circle. The scythe becomes the conduit through which his mental objective is accomplished, a tool for the embodiment of action as the body might be thought of, in Cartesian terms, as the mind’s instrument.

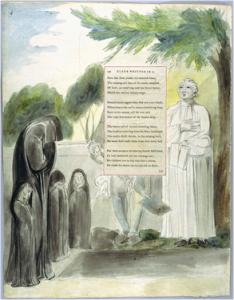

Elsewhere Blake utilizes the paper and pencil medium to simultaneously foreground labor while visually erasing the laborer, as in figure two, where he cuts a rectangular incision into the illustration in order to mount the letterpress text from Gray’s poem, removing the laborer’s head, shoulders, and abdomen but leaving his hands, legs, and shovel. Labor’s absence-presence here inverts the centralization of labor in figure one, a contrast between visibility and occlusion on which Blake capitalizes throughout the series, pitting laborers against the moneyed class (the priest, for instance, in figure two).

Fig. 2 “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard,” Page 4. Pen and ink, watercolor over pencil. c. 1797-98. Yale Center for British Art. (Image taken from the Blake Archive.)

By contrast, Blake’s engravings are starker, featuring fixed borders between subject and object. Those borders are not only visually striking, the manner in which the rolling press physically pushes the copper plate into the page leaves a material indention, detectable by running one’s fingers over the front of page. In late copies, Blake began printing solely on one side of the paper, and those borders are distinctly visible on the back, underscoring just how deeply entrenched those material borders actually are. The indentations recall the actual labor that went into making Blake’s books, even if what is represented does not necessarily draw attention to its own making.

Embedding thought in form, Blake models the colliding temporalities he describes in “Auguries of Innocence,” generating a theory of presentism that permits his readers to transcend historicism’s “separability.” If we understand Blake’s specificity not as mere particularity but as itself a tool for thought, scholars of Blake and of the nineteenth century more generally might circumvent the othering effect that arises as we unearth the “dense alterity of the past” (Levine). If we take nothing else from Blake’s books, it is that time is linked to material reality and that to study any object at any level of specificity is to partake in a diachronic relationship between the present and the past—between when the object was made and when we hold it in our hands—one that requires us, if we are to do anything more than catalogue, to engage text-objects not just in but as the material forms in which they were originally produced.

Milton, copy C, plate 1. 1811. Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

Georgetown University

Works Cited

Blake, William. The Complete Poetry & Prose of William Blake. Ed. David V. Erdman. New York: Anchor, 1965, 1988. Print.

Frye, Northrop. Fearful Symmetry: A Study of William Blake. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1947, 1969. Print.

Kornbluh, Anne and Benjamin Morgan. “Introduction: Presentism, Form, and the Future of History.” Presentism, Form, and the Future of History, special issue of boundary2 online 1.2 (2016). Web. 3 January 2017.

Levine, Caroline. “Historicism: From the Break to the Loop.” Presentism, Form, and the Future of History, special issue of boundary2 online 1.2 (2016). Web. 3 January 2017.